Jun 11, 2007

One of my favorite terms in the world of Web Content Management is "baking vs. frying," which refers to when presentation templates are applied to render pages out of structured content. Baking style rendering systems generate pages when content is published. Frying systems generate pages on the fly when they are requested by the end user. Whether a system bakes or fries content tells a lot about its architecture and what it is good at. Baking systems are great for high volume sites that do not need to personalize content. Frying systems excel when requirements include personalization, access control, and other presentation logic that uses information about the user in order to decide what to show and how.

While "baking and frying" does a great job of describing how a system is designed, there are lots of slight variations on how to implement a WCMS that are repeatable enough that they deserve names too. Here are a few.

Web Content Application Framework

When a frying style CMS has a decent templating language and a other good web application framework functionality (such as user sessions and profiles, a controller to manage URLs, and the ability to import custom and third party libraries) it is very tempting to start building applications on top of it. In the open source world, you see this happening all the time with projects like Drupal and Plone where you can download and install application like modules (for instance a shopping cart or an issue tracking system). Products like FatWire position themselves as tools for building dynamic content centric applications. There is nothing inherently wrong with this strategy but it does run the following risks:

-

Lock-in. Most of the code that you write on a CMS is not portable to another web application framework. You can mitigate this by writing as little logic as possible in your page templates. Code in classes is easier to reuse.

-

Sub-optimal application design. CMS presentation tiers are designed for displaying information. While they may have some transactional capabilities, they may not be as good as a pure web application framework designed for transactions. You might find yourself doing funny things like making dummy pages in the CMS so you can have a URL that a form can post to.

-

Depending on the licensing model, scaling up the architecture for high traffic and fail-over redundancy may be very expensive.

Published Static HTML

Static deploy is the classic baking style presentation pattern of generating static HTML files. Nothing special to talk about here other than the fact that this design does not support any server side interactivity. No server side activity means that you can deploy the site across a farm of inexpensive web-servers, making your website infinitely scalable. If your site serves 200 million content-rich pages a day, this model is probably your only option (unless you are Google). You can do things like add AJAX libraries to third party services for features like comments, record site traffic, and pulling in dynamic content. Companies wanting to get a little more interactivity into their managed pages will often use their baking style CMS in a Published View Code pattern. That is next.

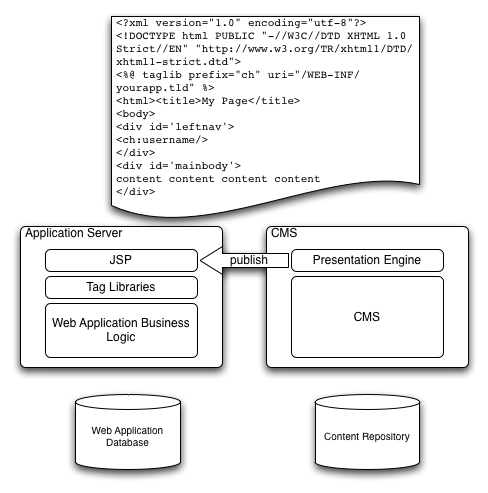

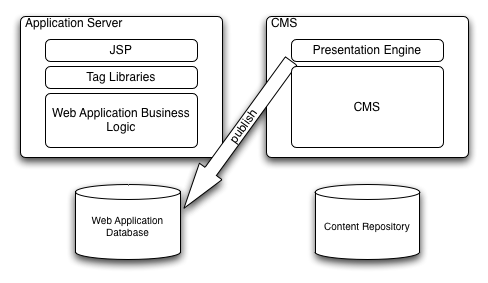

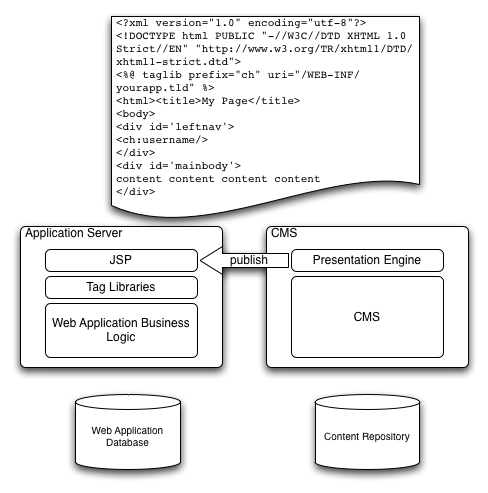

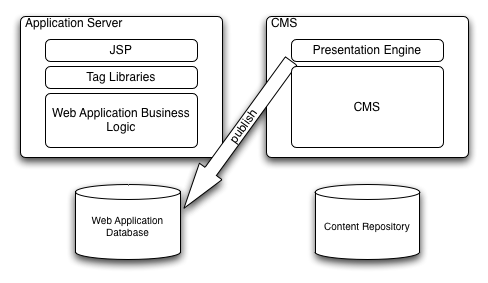

Published View Code

Also called "parbaked," Published View is when your baking style CMS writes out un-executed scripting or templating code rather than just static HTML. This code is then executed at request time for a dynamic user experience. At the very low end, this could just be server side includes or simple show/hide conditional logic. At the high end, it could be the View component of an MVC pattern. This hybrid model has some performance advantages over a fully dynamic site and gives the architect some flexibility as to what presentation technology she can use. There is also less lock-in because most of the complicated application logic is written into a presentation tier that will not necessarily be replaced when the CMS is swapped out. This design is also great for when you want to slowly phase in a CMS to manage a site that is already written in a scripting language because dynamically generated scripting code (from the CMS) can coexist with hardcoded scripting code. Keep an eye out for the following risks:

-

This design complicates the MVC pattern a bit because part of the "model" is baked into the "view." Once the MVC pattern gets kind of broken, it is a slippery slope to start baking more and more model type stuff into the view.

-

If you are layering CMS generated views into an MVC architecture with its own controller (that takes in requests and routes them to the appropriate pages), the CMS is going to have less control over the website than it thinks it does. URLs are going to be different so links may break. Preview can (and probably will) be a problem.

-

The developer may need to work on two systems that require different kinds of skills. Different departments may even need to get involved.

-

Because there is application logic being executed at request time, the delivery environment will require more computing power. However, you will not need to buy CMS licenses for all the servers on your web farm.

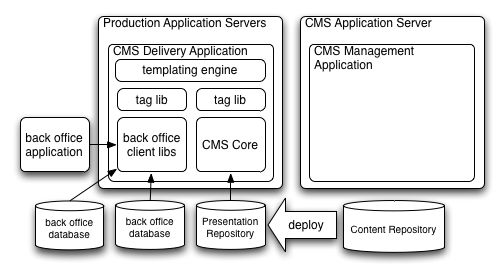

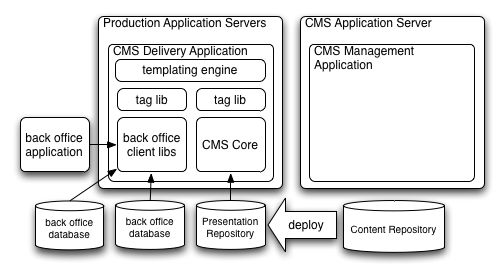

Structured Publishing

Structured Publishing is when your CMS publishes content as XML or rows in a relational database rather than pages on a website. A totally decoupled presentation tier then reads from this "presentation repository" to deliver the website. Structured assets can also be delivered at request time through a web services or a ReST style API but this requires a lot of computing power on the CMS and some good caching technologies on the delivery tier. In this model, the CMS has little or no control over the organization or behavior of the website. I wrote a blog post about this design a while ago so I won't repeat myself here. This design tends to work the best when content authors are not writing with one presentation channel in mind (for example if they are writing for print, web and sms, they tend not to get too wrapped up in the display on any one channel) and there is a separate group of people that are solely focused on the layout and behavior of the website.

Depending on the WCM product that you are working with, these patterns may be more or less obvious but still possible. For example, frying style WCM systems are designed for the Web Content Application Framework model. However, I have seen plenty of customers use a tool like wget to take a static HTML image of a dynamically generated website to deploy to a simple web server farm. The Enfold Entransit product allows content to be produced in Plone (a frying style system) and then publish structured content to another delivery tier.

I have seen all of these patterns succeed and fail to varying degrees. The biggest driver of success is knowing when to use a pattern and when not to. You need to look at your requirements - both the immediate ones and the long term vision.

Jun 04, 2007

For the past month or so, there has been a lot of activity on the Apache Lenya list about pulling the trigger on the much awaited 1.4 release. For those of you who have not been following this project, 1.4 has been "just around the corner" for what seems like an eternity. After bringing a few new of committers into the fold, it seemed like the project had the momentum to push 1.4 over the hump.

The project was obviously rusty on doing a major release. The 1.2 series has been around since the middle of 2004 and the project was getting comfortable maintaining and incrementally improving it. The dev mailing list has some interesting discussion about code freezes and what to do when you find a blocker right before cutting a release candidate. It is a thought provoking discussion if you are puzzling over the same issues. In the dialog, Gregor Rothfuss sent out this very interesting link to Jonathan Corbet's article A Tale of Two Release Cycles.

The article compares two projects: The Linux Kernel and the GNU Emacs editor. The Linux Kernel has a system of stable and experimental version numbers. Evens (like 2.6.x) are stable, odds are experimental. But the stable releases are not always so perfect right when they come out. Linus's philosophy is that the longer you wait on a release, the more complex it gets. It is better to just get it out, even if it has a couple known bugs. Users of Linux know that the operating system is not without its bugs. However, these bugs are usually are well documented and they are normally tolerable for even demanding, high availability applications. People (techie sysadmins and power uses) who like Linux and keep their kernels current recognize these issues and plan for them. More casual users of Linux go with highly managed distributions like Red Hat Enterprise Linux or SUSE Enterprise that have their own release cycles that buffer their customers from the new releases.

Emacs, conversely, has yet to do a major release since October 2001. Richard Stallman has set the tone that software should not be released with known bugs (that is an exaggeration but you get the idea). The Corbet's article is critical of Emac's long delays saying "It's not only users who get frustrated by long development cycles; the developers, too, find them tiresome. Projects which adopt shorter, time-based release cycles rarely seem to regret the change."

While I agree with the principle of "release early and often," much of depends on the context. For example, Emacs was probably not hurt by a slow release cycle. The Emacs users I know love the editor because it is familiar to them and they have built all of these macros and shortcuts to make the software their own. New hardware and new computing demands probably make it more important to push a operating system kernel forward aggressively.

To bring the topic to content management, a lot is going to depend on the user community. Some business users are looking for stability first and features second. Other users get excited by new versions of the system and are willing to report bugs and do work-arounds until they are addressed. If you have users like this and can build a partnership where they want to work with you to push the software forward, great! Ideally, the architecture is modular so the core of the application remains reliable and stable while new experimental features (that may be a little rough around the edges) are released. You can look at Emacs this way. The core application stays the same but users are constantly playing with their own new customizations.

Most importantly, projects should adhere to a release schedule to prevent the build-up of unreleased features that will become a regression nightmare when the version is finally released. Preview releases are also a good idea to keep the more daring/tolerant users of the software engaged. This is the best time to get feedback on the new concepts you are exploring. You don't want to know that a feature is useless after you got it "perfect."

Jun 01, 2007

Alfresco and Liferay are hosting a CMS/Portal user group meeting in Ontario, Carlifornia on Wednesday July 18th. I attended the last Alfresco user group in Boston and it was really good. Based on feedback from the Boston event, they are making this meet-up longer and more round-table focused. to quote:

"Content management and portal software enjoy a natural synergy that begs to be exploited. Join us as we share our knowledge and discuss best practices, integration topics, roadmap ideas, and much more."

Liferay and Alfresco have an interesting partnership. They come from very different backgrounds. Liferay started out as a project for a local church and grew into one of the most popular open source portal systems around (in a very competitive portal market). Alfresco's heritage is in large companies like Documentum and Interwoven and they have quickly become one of the most recognizable names in open source content management. The two companies were brought together by customers who were using both of their products to build content-centric web applications. Although, early releases of Alfresco had options to run Alfresco within JBoss Portal, the integration was pretty weak. More recently, LifeRay announced that would offer a LifeRay portal/Alfresco bundle. I haven't tried it out yet, but here are the instructions if you want to give it a go. After that you can go to the user group and let everyone know what you think!

May 29, 2007

A while back, I wrote a post on selecting a CMS. I have since gotten requests for more step by step instructions. While, the process is not so formulaic that it can be written into a recipe, this is the Content Here approach. This methodology is optimized for the complex content management projects. Some of the steps require a deep background in the content management marketplace or help from an expert. But here they are.

-

Document the content types. Before doing anything, you need to know about the content that is to be managed: its structure, frequency of creation and updates, and who is responsible for it. Usually, this is a good time to visualize better ways of structuring, organizing, and managing content assets.

-

Document the scenarios. Write short, narrative-based scenarios describing what the system will be used for and how. Stay away from implementation specific details as much as possible. For example, rather than say "the user clicks a 'check spelling' button and the system lists misspelled words," say "the system notifies the user of misspelled words." This leaves it open to the product to determine the best way to meet the requirement - is it with color underlining as the user types?

-

Document the legacy systems. Most Content Here clients require integration with legacy systems. It is important to understand them, how they are deployed, and their interfaces. A diagram showing the existing enterprise architecture and how the content management platform fits in is very helpful.

-

Filter by technology. While content management is all about usability, start by developing a short list of products that are technically capable of meeting the requirements. The biggest reason for doing this is that evaluating for usability is such a subjective and intensive process and it is impractical for both the customer (and the vendor) to demo more than a couple of products (you will see this later on). You might have some non-functional constraints like the system has to be customized in Java or run on Windows. To do this step effectively, you really need to be immersed in the marketplace and know the different products and who is using them for what. Buy a CMS Watch report (WCM or ECM) or hire a consultant (like Content Here) or, better yet, do both. Based on the questions that I get, I think that sites like CMS Matrix are more likely to confuse you than help you.

-

Filter by price. If a product is way beyond your price range, you should either filter it out or see if there alternative licensing models that meet your budget.

-

Engage with the vendors. If you have been following the steps 1 through 5, you should understand your content management requirements and have a short list of 3 or so products that would all probably work in your environment. The next step is to find the product that your users will feel the most comfortable using. Hopefully, the software vendor understands your needs and will partner with you to meet them. If two products are very close functionally, I tend to go with the vendor that will be more helpful in the initial implementation and beyond. This is where I think the traditional RFP process is broken. Rather than create a formal procurement process that tries to compare "apples to apples," you want an informal, interactive process that will highlight the differences between the vendors and their approaches. You want to share as much information with them as you can. If you don't trust a vendor, they should not be on your short list.

-

Prototype and learn. Because each vendor on your short list has a good chance of winning the deal, and you are not giving him a 100 page RFP to answer, he should be willing to invest the time to build a prototype that will demonstrate how his product will support your content types and usage scenarios. If an open source product is on your short list, consider building your own prototype or paying a systems integrator to do it (this will give you an idea of what it is like to work with the systems integrator). You should evaluate the prototype as actively as you can. Ask what can be changed and how. Ask the vendor to give you access to the prototype so that users can play with it at their own desks. Have your users think outside of their normal day to day and be innovative. Teach them about best practices in content management.Hopefully, the prototype demonstration was like a training session so the business users are comfortable finding their way around the system. If you intend to have your technical staff help with the implementation and/or maintenance of the system, now is a good time to request the developer documentation and access to the customer support site. Schedule a technical session where the prototype builder walks through the code and configuration that he did to build the prototype.

-

Project what an implementation would look like. To get an idea of the total cost of the solution, do a project planning exercise of what it would take to implement the solution and customizations and migrate your content. You will be better off if you plan for an iterative deployment where the first release supports the bare essentials and subsequent releases layer in more functionality. This is especially the case when your users are new to content management or have been using a limited toolset. They will learn so much about their needs from the first release and have wonderful ideas for improving and extending the system.

There you have it. Eight easy steps to select a CMS.

May 24, 2007

I will be presenting at the Web Content 2007 conference in Chicago next month. This is a first time conference with a great speakers list. If you register before June 1, you save a hundred bucks. Hopefully I will see you there.

A couple of days later, I will be on an Enterprise Search panel at the Enterprise 2.0 Conference in Boston. I think this one is going to be interesting because my co-panelists all come from search software vendors. There is an interesting tension between the content management market and the search market. Content managers and information architects focus on organizing and structuring content to make it more usable, accessible, and findable. Nirvana for search vendors is not having to care about how the content is organized and stored. Of course, everyone can agree that the content must be worth finding. That may be the common ground that we can all start working from.

May 11, 2007

David Neuscheler, CTO of Day Software, was just nominated by the JCP for the Most Outstanding Spec Lead Award for his work on JSR 283. JSR 283 takes the Java Content Repository (JSR 170) further by adding enhancements like federation, remoting, more standard node types, and better access control. JSR 283 was first introduced in October 2005 and these things typically take a long time to make their way through. In the first go around with JSR 170, the team kept momentum by building an open source reference implementation: Apache JackRabbit. According to Zukka Zitting, JackRabbit (or at least a branch of it) will be used as a reference implementation for JCR 283.

May 07, 2007

James Robertson just posted another great article on usability called 11 usability principles for CMS products. I think all of these principles are worth keeping mind when selecting or building a CMS (or any software for that manner). In response, Adriaan Bloem of Radagio posted this great comment on the CM Professionals mailing list:

Much of what makes web 2.0 examples work is based on the fact that in one way or another their use is much more intuitive than that of "classic" content management systems. Everyone can relate to the fact that a blog places the newest item on top; or that a wiki links through keywords; or that you can simply enter a couple of tags on a photo site and you'll be able to search those. "They make it look so simple", yet what we see in CMS interfaces is another turret, flag or tower on the castle and a little bit of AJAX thrown in to be buzzword-compliant.

I can't even count how many CMS products have added drag and drop sorting to their old "operating system" of a user interface just to claim they understand and deliver a Web 2.0 experience.

May 03, 2007

If you have been holding out for OpenCms to come out with version 7, your wait is almost over. The OpenCms team just announced that the first release candidate (RC1) is available in CVS and will soon be packaged for download on www.opencms.org. The stable version is expected to be out in July.

For perspective, v7 is probably as big an upgrade as v6 (released 2 years ago) was over v5. Whereas v6 introduced in-site editing functionality (called "Direct Edit") and better support for structured content, v7 brings goodies like WebDAV support (now developers can use their favorite IDE to edit presentation templates!) and a dependency engine that will do a better job of managing links and automatically publish related content (so an image will be published if the article that references it is published). Version 7 will also have much improved user management. For a list of other enhancements, check out the press release.

Apr 24, 2007

SDL International just announced that they will acquire Tridion. This is very interesting news because The Netherlands based Tridion seems poised to make quite an impact on the North American mid level WCM market. They have just started to aggressively market in the States and the product is already popping up on selection short lists that typically include Ektron and SiteCore. SDL is a combination software/services company focused on global information management. Not long ago, they acquired Trados.

Apr 23, 2007

The second installment of our three part series on Web 2.0 content management has been published on CMSWire. In this article Brice and I discuss how a Web 2.o enabled WCM product should serve three audiences: internal content producers, the external human audience, and the machine or software audience. As always, feedback is welcome.