Jan 19, 2010

Warning: this post is highly technical. Non-programmers, please avert your eyes.

Deane Barker (from Blend Interactive) and I have a running conversation about CMS architectures. One of the recurring topics is how content models and other configuration is managed. There are two high-level approaches: inside the repository and outside the repository. Both have their advantages and disadvantages.

-

Managing content types outside the repository

My preferred approach is to manage content type definitions in files that can be maintained in a source code management system. This way you can replicate a content type definition to different environments without moving the content. Developers can keep up to date with changes made by their colleagues. Configuration can be tested on Development and QA before moving to production. There is no user-interface to get in the way. No repetitive configuration tasks. Everything is scriptable and can be automated. I especially like it when content types are actual code classes so you can add helper methods in addition to traditional fields. Of course, when you get into this, it is a slippery slope into a tightly coupled display tier that can execute that logic.

On the downside, it is often difficult to de-couple the content (which sits in the repository) from the content model (which defines the repository). When you push an updated content type to a site instance, you might need to change how the content is stored in the repository. This is more problematic in repositories that store content attributes as columns in a database. It is less of a problem in repositories that use XML or object databases (or name-value pairs in a relational database) where content from two different versions of the same model can coexist more easily.

If you do manage content type definitions outside of the repository, a good pattern to follow is data migrations, which was made popular by Ruby on Rails. I am using a similar migration framework for Django called South. Basically, each migration is a little program that has two methods: forward and back ("up" and "down" in RoR. "Forwards" and "backwards" in South) that can add, remove, and alter columns and also move data around. The forward updates the database, the backward reverts to the earlier version.

- Managing content types within the repository

Most CMSs follow the approach of managing the content type definitions inside the repository and provide an administrative interface to create and edit content types. This is really convenient when you have one instance of the application and you want to do something like add a new field. There is no syntax to know and application validation can stop you from doing anything stupid. Some CMSs allow you to version content type definitions so that you can revert an upgrade.

When you have multiple instances of your site, managing content types can be tedious and error prone if you need to go through the administrative interface of each instance and repeat your work. Of course, you can't copy the entire repository from one instance unless you want to overwrite your content. If your CMS is designed in this way, you should look for a packaging system that allows you to export a content definition (and other configurations) so that it can be deployed to another instance. Many CMSs allow an instance to push a package directly over to another instance. The packaging system may also do some data manipulation (like setting a default value for a required new field).

Unless you are building your own custom CMS, this all may seem like an academic question. It really is quite philosophical: is configuration content that is managed inside the application or does it need to be managed as part of the application. The same thing goes for presentation templates (but that is another blog post). However, if you intend to select a CMS (like most people should), it is important to understand the choice that the CMS developers made and how they work around the limitations of their choice. If you are watching a demo, and you see the sales engineer smartly adding fields through a UI, you should ask if this is the only way to update the content model and if you can push a content type definition from one instance to another. If the sales engineer is working in a code editor, you need to ask how the content is updated when a model update is deployed.

Jan 11, 2010

Normally I don't worry too much about search engine optimization when I write blog posts. My writing is as much for organizing my own thoughts as it is to drive site traffic. My philosophy on search engine optimization is to produce good content and avoid hindering search engines indexing my site. Good content is clear, well organized, and useful. Not hindering search indexes means being text-rich, minimizing broken links, returning the appropriate status codes, and keeping HTML simple. I am not going to trick anyone to come to www.contenthere.net but if I have something that would useful to someone, I want it to be found.

After reading the title of a recent blog post ("The biggest thing since wood pulp"), I realized that I was breaking my own very lax rules. My attempt at a pithy title was effectively hiding what the article was about: a possible consequence of the Internet's disruption of the newspaper business. I looked at my recent posts (see screenshot) and realized that I do this quite a lot. One of my worst offenses is "Doubt," which offers an alternative to to matrix-based decision-making. Most people probably assume that I am talking about the movie of the same title. Another example is "Another Flower War", which is about a dispute between Magnolia the CMS and Magnolia the social bookmarking site. I know this title was misleading because I was getting comment spam for garden supply retailers.

Pithy titles may be effective in print media when the reader has already made the investment to browse through the publication and is looking for things that spark his interest. They may be marginally effective by causing a curious RSS subscriber to click through. But they are totally counter productive in a search result. Even if the search engine thinks that your article might be relevant to the query, the searcher is likely to assume that your article was listed in error as he scans the results. You have just done the searcher a disservice because you have hidden the answer to his problem.

To some extent, some open source projects share in this problem. Sometimes open source project names are taken from an obscure (nerdy) cultural reference or something to do with the history of the project. Sometimes project names are just intended to be fun. I remember an Optaros colleague telling me how silly he felt when he was talking to a CIO and suggested that they use Wackamole for network monitoring. A lot of insiders have to try and recommend a project with a silly name for it to get credibility in the mainstream.

Overly clever titles are an inside joke that excludes potential new readers. It's a little like giving a tourist directions that reference where a Dunkin' Donuts shop used to be. These names are useful in getting the attention from the old guard but they exclude the newbies. This may be an intentional community dynamic where new members need to demonstrate their commitment in order to get accepted and longstanding members feel bonded by their shared knowledge. But, if the goal is to bring outsiders in, the name of the project or an article should be clear and not overly silly and obscure.

Jan 07, 2010

One of my favorite podcasts, Planet Money, recently did a segment on bias in journalism. Apparently, back in the 1870's, most newspapers were blatantly affiliated with a political party. In fact, their bias was openly stated in their mission statement and it was part of the newspaper industry business model. In return for political support, a newspaper publisher would get lucrative contracts for printing government documents and cushy government posts like postmaster. You historians will remember that Ben Franklin, himself a publisher, was the first postmaster general. The newspaper publishers didn't do this because they were greedy or unscrupulous; it was hard to make a living publishing a paper any other way. The cost of printing and distributing a paper was more than the audience could afford. Given the options of the low return of serving an audience that can't afford your product or the high return of serving a political party, the choice was easy.

But then a big technology disruption happened that drastically cut the cost of publishing a newspaper and all of the sudden made the business more profitable. It wasn't the Internet, it was cheap paper made from wood pulp. Up until that point, the news was printed on rag paper like what our dollars bills are made of. With cheaper paper, a publisher could lower the price and get a higher volume of sales. You could sell even more papers if you had higher quality news. More newspapers entered the market but there were still barriers to entry to preserve profits. Even though the variable cost of the papers was low, the up front fixed costs of the presses and distribution channels kept competition manageable.

Like wood pulp, the Internet also disrupted the news business but in a different ways. While the Internet has reduced the cost of distributing the news (especially over large geographic areas), it has also driven the revenues down. Most importantly, the classifieds business has been eaten up by sites like Craigslist. Advertisers have other options to reach a more targeted audience than general news can. And, of course, there are no barriers to entry. Even an schmo like me can have a blog.

Will the decline of profitability push publishers back to bias? There are some concerning signs. Not so much with the big media brands (although you could definitely make the argument that all publications have their leanings), but there are plenty of examples in blogosphere (and Twitter) where bloggers are paid to promote a product or political agenda. The distinction between professional and amateur media is blurring. We tend to follow people (professionals and amateurs) who share our passion (usually on very narrow topics) and we unsubscribe when they lose our interest or confidence. But very few people are getting rich on having us as an audience — not until they sell out and exploit our trust. Then we will leave as quickly as we came because there is bound to be a fresh new voice that values our attention as unprofitable as it may be.

As an audience that wants to be informed, we need to do two things.... First, we need to figure out a way to compensate for the value that we enjoy. There have been some interesting ideas of establishing non-profits and public-media style structures. Second, we need to become very good critical thinkers. We need to be able to filter and verify the information that is bombarding us. We need to become our own editors if we can't immediately trust anything in print. I am sure that is what people did back in the 1860's did too.

Jan 04, 2010

I have finally gotten around to reading Clay Shirky's excellent book Here Comes Everybody

. I love Clay's writing style and the way his perspectives make me think. One of the points that really resonated with me was about open source. But before I get into it, I should say that when Clay talks about open source, he is really talking about community developed open source (not commercial or institutional open source). Readers of this blog know that the designation "open source" simply means that it is licensed under an OSI certified license. "Open source" says nothing about how the software was developed. Given that disclaimer, Clay nails it when he describes the advantage of community developed software:

The bulk of open source projects fail, and most of the remaining successes are quite modest. But does that mean the threat from open systems generally is overrated and the commercial software industry can breathe easy? Here the answer is no. Open source is a profound threat, not because the open source ecosystem is outsuccessing commercial efforts but because it is outfailing them. Because the open source ecosystem, and by extension open social ecosystems generally, rely on peer production, the work on those systems can be considerably more experimental at a considerable less cost, than any firm can afford. (from page 245 of the hard cover version)

This quote comes from a chapter called "Failure for Free" that discusses the importance of failure for innovation. The key point is that traditional companies can't afford to really innovate because they must limit their bets to initiatives that they feel have a high likelihood of success. Innovation winds up being constrained to small tweaks to things that are well known. Real breakthroughs are rare. Community development doesn't make better ideas but it reduces the cost (and risk) of trying ideas that at first seem unlikely to succeed. Out of all this experimentation comes unexpected successes. Even the failures provide useful data that can be turned into future successes.

When open source critics see the volume of incomplete or dead open source projects as evidence against the sustainability of open source, they are missing the point. A low success rate is critical to real innovation; but that is hard to understand by someone for whom failure is discouraged or not tolerated at all. It is widely accepted that the best design for an experiment is one with a 50% chance of failure: if you know what the outcome will be, the experiment is not worth doing. But if the cost (in time and resources) of the experiment is zero or close to it, the ideal failure rate is much higher.

While we have seen many examples of community developed software out-innovating its commercial peers, this phenomenon has very little to do with open source. An open source license can create an environment that invites contribution by reducing the risk that one will exploit and unduly profit from another's contribution. But what is more important is how the software is managed. Most successful open source projects have adopted an architecture consisting of a core that is tightly managed for stability and quality and is extensible by adding modules. The bar for module code is considerably lower than core code. This allows an open and dynamic community to experiment with new ideas. The community not only bears the cost of failure but it also brings in new perspectives that the core maintainers don't have. Some of these extensions will be absorbed into the core or will become part of a commonly used bundle. Others will wither and die.

This pattern of stable core and innovative fringe does not have to be unique to open source. It doesn't really matter how the core is licensed if entry into the fringe is open. The one area that open source licensing helps with the core is in achieving a level of ubiquity that attracts a community. High licensing fees or the bottleneck of a traditional software sales process can limit the size of the user base and discourage contribution. The community developer needs the promise of a large user base to justify the time investment of contributing his work. But open source is not the only way to achieve a large user base and there are plenty of examples of commercial software and SaaS user communities that have a successful code sharing ecosystem. One company that is particularly successful is Salesforce.com. Salesforce has created a very powerful API and module packaging framework. More importantly, they have priced the product to penetrate small-medium sized companies and non-profits. In particular, the Salesforce Foundation makes the product very inexpensive for non-profits. These strategies have infused the customer population with lots companies that are highly motivated to share. These customers are active both within the AppExchange community and also integrating 3rd party open source projects like Plone (see Plone/Salesforce Integration) and Drupal (see Salesforce module).

On the flip side, there are plenty of commercial open source software companies that not been able to leverage community development. There are two primary ways an open source software product can prevent community development from flourishing. First, there can be factors that limit adoption of the core like in the case of open core products that discourage the use of the open source version. Second, the architecture can be monolithic so the only way for an outsider to add a feature is to fork the codebase. All a software producer has to do is solve those two problems. The supplier doesn't even really need to provide tools for sharing code. If the install base is large (which usually means the software is useful) and the architecture is modular, developers will find a way to communicate and share code. They can use services like Google Code, GitHub, or SourceForge to collaborate. Too often companies put code sharing tools in place without solving those two problems and then complain when they don't see any activity. In many cases, the user audience is too small to support a contributing ecosystem. In other cases, the incentives are not lined up appropriately. Shirky calls the three ingredients of a collaborative community: promise, tools, and bargain. The promise is what the contributor can expect to get out of participating; the bargain is the terms and rules for participating. Open source licensing helps with the promise and the bargain. The open source promise is that others may help improve your code. The open source bargain is that people can't take exclusive ownership and profit from your work. Some communities, like Salesforce and Joomla! have thriving commercial extension marketplaces. In those cases the promise and bargain are different but they are very motivating.

Any widely used software application, if it is appropriately designed, can benefit from community development and the benefits are not limited to the successful contributions. Perhaps the biggest value of community development is increased innovation through reducing the cost of failure. In order to harvest this value, a company needs to actively monitor, analyze and participate in its community. There is a goldmine of information sitting in the chaff of failed contributions as well as the modules that do gain traction. Companies that ignore this value do so at their own peril.

Jan 01, 2010

Thank you to all my clients, colleagues and readers for making 2009 another great year. I wish you all a healthy, fulfilling, and prosperous 2010!

Dec 18, 2009

This post was originally written as a comment on Jon Mark's excellent post Visions of Jon: WCM is for Losers but it got out of hand and I suspect that it is too long for a comment so I am re publishing it here.

Thanks for the great post Jon! I have to agree with you that the term Web Content Management System is misleading because of its diverse focus on multiple publishing channels. You probably remember that in the old days (~1996), the term "CMS" was first used to describe products like Vignette and what are now called ECM systems were just called Document Management Systems, Records Management Systems, etc. When the big DMS vendors started to covet the term "content," the (then) smaller WCM vendors had to slide over a bit and qualify their category with a "W." Then some of them started to ruin themselves by trying to expand into document, management, records management, etc. - but that's another story.

But enough about the Ghosts of Christmas Past... I agree with the point that a WCMS has multiple aspects. I would name three: a management tier to edit semi-structured content, a repository to store the semi-structured content, and a rendering tier to render the content. Usually the repository is more tightly coupled to the management tier so it is often tucked into the management application. In fact, the three components are often bundled for convenience.

In my mind, what sets WCM apart from the other forms of CMS is the C. I still think of Content as having more structure (and less embedded formatting) than what you typically find in an ECM repository. In the ECM world, the structured information is called metadata and is not considered part of the asset (a MS Office file that jumbles together information and presentation). A WCM asset needs to be rendered (given a format) to be useful to a consumer. This is why a WCMS needs a good rendering system.

Most ECM assets can just be downloaded but the range of formats they can take is limited. You can get a different file format (like a PDF) or a different scaling or cropping of an image but the output looks essentially the same. ECM has tricks to add structured information like metadata and embedded tags but that is going against the grain. WCM, which is inherently structured, knows what each of the different elements of an asset mean. I like to say that ECM is documents pretending to be content and WCM is content pretending to be documents. That is, ECM starts with a document and tries to pull information out of it while a WCM starts with structured information and renders it into a .html, .pdf, .xml, or any other kind of document.

So, at the end of it all, I would say that WCM should be renamed back to CM and ECM should be renamed to EDM: Enterprise Document Management.

Dec 17, 2009

I have been catching up on product demos recently and have seen some really elegant functionality for marketers. Several products have introduced modules that allow CMS users to plan, implement, and measure multivariate testing, search engine optimization, and personalization without the continued support of a developer. A developer has to put the tools in place but, after that, the CMS user can fully control the behavior of the site and optimize its business impact.

It is easy to get excited by this functionality. But then you think of the difficulty your average organization has with even the basic aspects of content production and you wonder if they ready for these tools. How can you do an A/B test if getting someone to write option "A" is a struggle and option "B" would be a miracle? Of course, not all companies suffer from these issues. The more sophisticated publishers and eCommerce companies have been doing these advanced site management activities even when the technology stood in their way, much less facilitated them. But your average marketing site is still in the dark ages when it comes to managing content.

Will your average marketing group be able to leverage this functionality? Or will it be yet another unused feature that clutters the user interface? My hope is that once contributors and site managers start to experiment and see results, they will rapidly evolve to be more committed and proactive in the same way social media participants started to embrace tagging when they saw their work start to surface in more prominent places. A tight and accurate feedback loop is important in any learning process so maybe access to testing and metrics has been the missing feature rather than usability-oriented functionality like in-context editing. It is probably more effective to make a task interesting and rewarding than to make that uninteresting work easier to do. The former strategy will cause a user to overcome any obstacle he is faced with. In the latter strategy, there will always be some excuse not to do the work. I touched on this idea in an earlier post called "What your intranet needs is a publisher!"

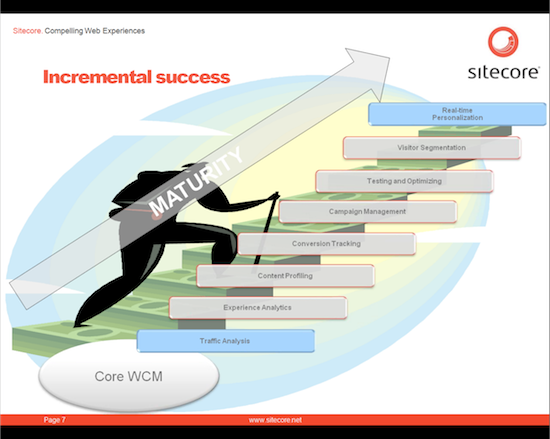

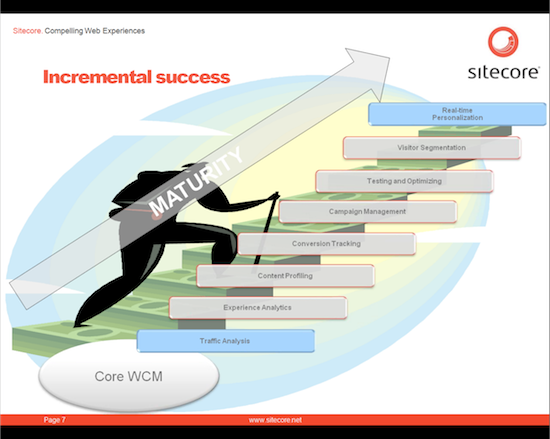

That is not to say that all you need to do is drop in personalization functionality one day and your organization will immediately change. I have seen many organizations fail with this approach because they didn't have the content to support it. I saw a slide from a Sitecore (below, click for a larger image) demonstration that shows a gradual maturity process that begins with understanding your users and your content and ending with real time personalization.

I very much agree with the model but I think that the trick to success is being able to see real results at every step of the way. Most organizations will not have the commitment to sustain a continuous effort through long periods of no results. Results are easy to felt from the conversion tracking step onward. Getting to that point, however, will require organizations to aggressively push through traffic analysis, experience analysis, and content profiling. Perhaps there is room to get some intermediate outcomes along the way that can keep an organization hungry for more. These outcomes can't just be in the form of a spreadsheet that is out of date by the time that it is presented. There needs to be some tangible business impact like being able to make a small change to the website that yields some measurable result. If this is not possible, the best one can do is time-box this period of no feedback and have faith that the results will be worth that fixed investment.

They are just coming on the market now but I am really looking forward to seeing the organizational response to these marketing tools. The early adopters will certainly benefit from the functionality because, by being early adopters, they have already shown their commitment to improvement. It will be really interesting to see examples of this functionality transforming mainstream organizations that have struggled in the past.

Dec 07, 2009

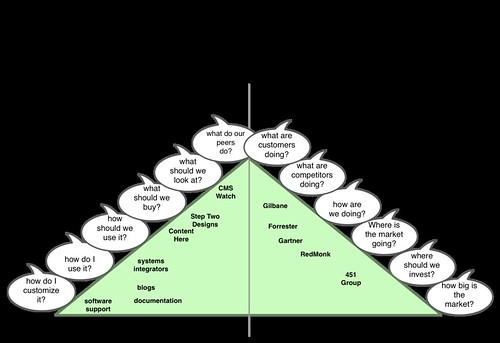

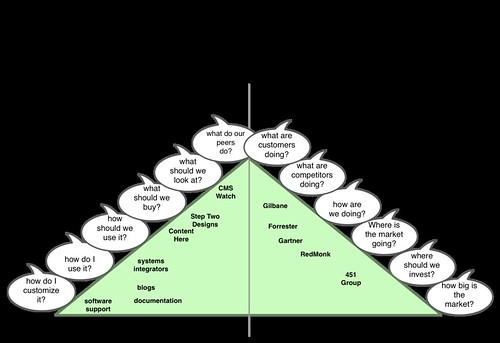

I generally dislike the "map of the market" approach to describing a software market because the actual use of software is too specific to be generalized into abstract dimensions like "high and low end" or "innovative." However, during a recent Content Here leadership offsite (OK, I went on a bike ride), I was thinking about Content Here's positioning in the marketplace and I found a picture to be quite helpful. This is what I came up with (click on the image for a larger view).

The primary point of the diagram is to show that consumers enter the information marketplace with different types of questions and information providers offer different types of answers. The intent of the question appears on a continuum that ranges from problem focused to solution focused. Technology buyers are focused on their business problems. As you progress towards the "problem" end of the spectrum, the questions get more specific and require intimate knowledge of the context and domain to answer. On the other end of the spectrum, the consumers (software vendors and investors) are trying to understand trends that will inform a business strategy for managing (or investing in) a solution. The information on the solution side gets very abstract and speculative because the solutions themselves are designed to be re-usable across many different kinds of problems and software companies need to build products that will be sold in the future. In the center of the spectrum is where the interests of the buyers and sellers converge. Here the buyers are thinking a little beyond the specific problems they are trying to solve today to where they need to be in five years. Here vendors are thinking beyond how their solution measures up today to what buyers need going forward.

All of these questions are important and the marketplace for answers has evolved to answer them. On the sellers side of the diagram, you have the major analyst firms who primarily serve the technology vendors. Their information can also useful to the CIO that is trying to understand trends but it will not be useful for a decision faced today. I didn't put too much thought into the positions of the "sell-side" analysts on the right side of the diagram. I would love input here.

I am more interested in the left side of the diagram — in particular, where Content Here is focused. My unofficial tag line for Content Here is "Content Here helps technology buyers be awesome at making decisions" (format borrowed from the Joel on Software article: "Figuring out what your company is all about"). Content Here tries to help client's answer the questions of what technology to buy and what do to with it. To play this role, I need a deep understanding of how the various technology products work — but not as deep as a systems integrator that specializes in that technology or the software vendor's technical support. Consequently, my reports are very technical compared to other analyst reports. I tend not to go as broad as CMS Watch because I stop keeping up with a product once I realize it is not relevant to my potential client base. Only when I hear that something has changed with the product do I check back (and this is why I don't publish a list of technologies that I follow or don't follow). Most importantly, I need to be able to rapidly discover a client's requirements through an efficient consultative process.

This hybrid approach puts Content Here in between a systems integrator and an analyst company in terms of detail. I am not surprised by low number of competitors because this is a hard place to be. I need to dig into the many technologies I cover by building prototypes and talking with implementors. I also need to understand the business aspects of how the technologies are used. I am always on the challenging slope of the learning curve. I can neither sit back and pontificate on the abstract nor enjoy the luxury of knowing every detail. As difficult as it is to be in this position, I can't think of a more stimulating business to be in.

That is as far as I have thought things through. I would love to hear your feedback on the usefulness of the concept and the positioning of the different players. In particular, if you are a consumer of information, is the information marketplace serving you with the appropriate level of detail?

Dec 04, 2009

I am catching up from a whirlwind of activity at the Gilbane Conference in Boston this week. I gave three presentations (below), organized a breakfast for open source CMS software executives, and had a great time talking with so many industry friends. It was particularly nice to meet people like Scott Liewehr (@sliewehr), Scott Paley (@spaley), Jeffrey MacIntyre (@jeffmacintyre), and Lars Trieloff (@trieloff) who I had known only virtually before. I wished I could have stayed for the third day of the conference but I had to get back to work. Everyone seemed to feel very positive about business and where content management is going so I left brimming with enthusiasm for 2010.

What follows is a brief run through of the presentations I gave.

On Tuesday morning, I did a presentation called Open Source WCM and Standards for the CMS Professionals Summit. To summarize, open source really has nothing to do with open standards but there are some areas where they converge. "Open source" describes a license. Any software can be open source if it is assigned an OSI-compliant license. Open standards is about software design — technology choices about what standards to support. That said, there are three areas where open source and open standards converge:

-

when an open source project is started to create a reference implementation for an emerging standard (note, on slide 5 I didn't say that Alfresco was created as a reference implementation for CMIS, you had to be there.);

-

when there is a chicken and egg problem of value and adoption (like RSS and now RDF) some open source projects have the install base to easily create widespread support and a lower hurdle create an implementation;

-

projects driven by developers tend to put a higher priority on aspects like integration and attention to technical detail than marketing driven products which are more feature oriented.

How to Select a WCMS

My "How to select a WCMS" workshop is turning into a signature presentation for me. There was not too much difference from prior presentations of this workshop except this time I went into more detail on using doubt to make a decision. At that time, my friend Tim McLaughlin, from Siteworx, had popped into the room. He told me afterwards that he agrees with the approach and even read a scientific paper that found that the best decision makers use this method of elimination for choosing. Tim, if you are reading this, you owe me that link!

One particularly interesting part of that worshop was that one of the audience doubted the necessity of content management systems in general. So I was put into the position of having to defend the industry. He was coming from an organization that was managing 100 very small, unique, independently managed, and unimportant websites. In this case, I had to agree and I used the metaphor of a factory. You don't build a factory to produce less than 10 units. A CMS would not help him until he started to try to manage all those websites in a more uniform way. For the time being, I suggested that he look into Adobe Contribute which handles basic things like deployment and library services without trying to manage reusable content.

I presented with Kathleen Reidy from The 451 Group on "The rise of Open Source WCM." Kathleen had some great slides talking about commercial open source vendors in the market. My presentation was from a buyer and implementer perspective. The general message was that buyers have the benefit of more choices and more information but they also have the responsibility to take a more active approach to selection. They can't expect an analyst firm or salesman to tell them what is the best product. They need to understand their requirements and implement a solution that solves their business problems. Open source software suppliers depend on customers doing more pre-sales work themselves and they pass that savings back in the form of no (or low) licensing fees.

The biggest disappointment was when Deane Barker misunderstood slide 5 and tweeted that I think that open source is like a free puppy. Of course, this was re-tweeted several times. As I have said, all CMSs are like puppies: some are free, some cost lots of money, but all require care and feeding. If you have the intention of owning a puppy and understand the costs involved, you appreciate that a free puppy is less expensive than a puppy that you have to buy. If you spontaneously come home with a a puppy just because it was free, you might be in for an unpleasant surprise. Similarly, if you adopt a CMS just because it is free and you have not budgeted for properly implementing a website, you will get into yourself into trouble. Later, Deane and I had a great dinner together with David Hobbs before I headed back home.

Nov 23, 2009

Over the past few years we have witnessed the transfer of website ownership out of the technology organization and into the department that owns the information. This has been a positive trend. While technology is certainly necessary to run a website, what makes a website successful is the content and its ability to communicate to an audience. Even though most I.T. departments recognize this, they have other systems that compete for enhancement resources and they often find themselves blamed for latency on web initiatives. Furthermore, technology is an easy scapegoat for more embarrassing organizational deficiencies like not having skilled and motivated contributors. Removing I.T. from the equation puts power and accountability squarely in the hands of the people who own the content (and the conversation) and removes any and all ambiguity about who to blame when the website fails to produced desired results.

As attractive as these outcomes are, transferring ownership is not comfortable. It puts a business manager into a position that he or she has not been in before: an owner of technology. Growing up through the ranks of leadership, most managers didn't sign up for planning technology projects, directing technical staff, or taking shifts on "pager duty." They purposely avoided a technical career track and neglected to build those skills. On a good day, they can ignore technology but on a bad day... well, we try not to think about those. Instinctively, the business manager wants someone who he can shout at (or hover over) until the issue is fixed. But who is that person and who pays him?

The first step is to hire a web development shop (systems integrator) to do the initial implementation. Even if you are an I.T. organization, I recommend bringing in a systems integrator who has significant experience on the platform you plan to deploy. These systems are extremely flexible, which means that there are plenty of bad design choices that you can make; you want to work with someone who has ruled out at least a few of them. But what happens after launch? An optimistic (naive, really) approach is to believe that, once the system is implemented, business users can just run it themselves. That doesn't work. Even if you are lucky enough to have no bugs and contributors that don't make mistakes, a successful web initiative attracts ideas for making it better. Ignoring those ideas is demoralizing to the users and causes them to dislike the solution.

In many cases, the business unit will create a retainer relationship with the systems integrator where the system's integrator plays the role of outsourced I.T. This typically only works when there is an internal staff member who plays the role of "product manager" and directs the external development team. Otherwise, the relationship can get very costly as hundreds of uncoordinated change requests start to degrade the usability and maintainability of the solution. It is also costly to have this external partner provide the first line of support. You don't want to pay consultant rates to triage "the Internet is down" and "I can't find the 'any' key."

If it is critical to the business that the website continually adapt to changing requirements and opportunities, it will expensive to maintain a team of consultants working on an endless enhancement queue. At some point, it will be cost effective to hire internal development resources to implement routine enhancements (like template changes). I think that more and more companies are falling into this category. The web is changing so fast. You need to try new things and continually improve.

Here are some staffing levels to consider:

-

__Infrequently changing website: __ one website product manager managing an external developer. The product manager also does training, contributor mentorship, and first line technical support (including pager duty to differentiate between an unplanned outage and "the AOL is broken."). The product manager should also maintain and interpret website analytics reports and Google Webmaster Tools.

-

__Continually optimized website: __ a website product manager with web developer skills. In this case, the product manager has the skills to reliably execute routine template edits and basic system administration tasks (configuring accounts and roles on the system, unlocking files, etc.). It is a good idea for the third party systems integration company to regularly review new code to suggest refactoring for quality, maintainability, and security. Like with the previous staffing level, the systems integrator is also brought in for larger, more complex enhancement projects.

-

__Steadily changing website: __ a website project manager managing an internal web developer. The web developer has solid DHTML development skills and is proficient in the template developing syntax of the WCMS. Like with the previous level, a third party systems integrator does periodic code review and executes larger enhancement projects. The development queue consists of a medium size (3 days to execute) enhancement, plus a steady stream of tweaks.

-

__Rapidly changing website: __ when I interviewed publishing companies for my Web Technologies for Publishers report series, I learned that most successful web publishing companies had a development team of between 2-5 developers and deployed new code as frequently as once per week. If your business is your website, this is the staffing level that you probably need.

Full outsourcing of all technology knowledge and ownership is not realistic. At the least, you need to have staff that understand the technology enough to know what to do and how to direct people to do it. How much you go beyond that depends on how aggressively you need to advance your platform.