Feb 02, 2009

Not that long ago, I started reading The Art of Community. Jono Bacon is posting to this blog as he writes an O'Reilly book by the same name. You can read drafts of the first chapters here and here. I expect demand for this book to be high because communities are valuable but very difficult to create. Companies often envy the passion and personal investment that some open source communities have been able to inspire and they get frustrated when their community building attempts fail to thrive. Jono has been involved with Linux and KDE and currently serves as the Ubuntu Community Manager for Canonical so he knows a thing or two about open source communities.

I have written on the topic of evaluating the health of a community and have been approached by more than one software company looking for that special sauce to help create a self-sustaining customer community. One thing is for certain, communities are not built on tools - it takes more than a forum or a wiki to make a community. Tools like these can help an existing community communicate better but they can't establish a community where there isn't one. A successful community requires a purpose worthy of passion (for a great discussion on this, see "Would you Join a Toothpaste Community?"), leadership to help people productively focus their passion, and methods for people to get value out of their participation.

So far, the best book that I have read about the community aspects of open source software has been The Success of Open Source

. The Art of Community will have a much greater focus on how to create a community. The table of contents looks like a manual for a community builder. One thing that I would like to see, but haven't yet, is a set of strategies for creating a passion-worthy purpose out of a seemingly mundane topic (like toothpaste).

Part of the writing process involves building a community of readers and harnessing their input. The project is still too young to see if there is any traction. I am looking forward to seeing how both the book and the community around it come together and if purpose, leadership, and value emerge.

Jan 28, 2009

Content Here's new Favicon

Marketing Vox has an article describing Google's plan to show favicons in search result listings (thanks AJ Kohn for the link!). For the uninitiated, favicons are those little pictures that sometimes appear to the left of the URL in your browser's address bar. This is an interesting departure from Google's text-only policy on search results and it gives webmasters a new way to distinguish their websites. For now, Google is only going to do this on site specific searches (like when you type "java web content management site:www.contenthere.net"). Google's sparse style could get very busy looking when cluttered with 10 little pictures per page. Speaking of ugly, does anyone like Google's new favicon?

Creating a favicon is easy. All you need to do is make a square image and then use a site like HTML-Kit to generate the favicon.ico file. Put it in your web root and then you are done. A little side benefit is that you won't see any more of those warning messages in your web logs saying it can't find the favicon.ico file.

Jan 27, 2009

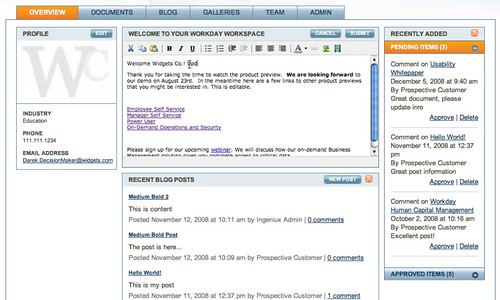

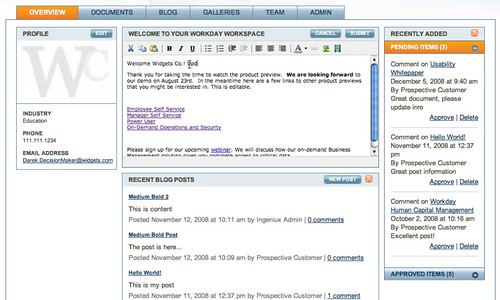

I talk to a lot of web content management software vendors and open source project leaders and it seems like most of them are working on some kind of "knowledge worker collaboration portal" - a SharePoint killer. At first they avoid this comparison (nobody likes to openly challenge Microsoft on its home turf; even now in the era of "I'm a PC, I'm a Mac"). But eventually, they admit that is exactly what they are doing.

To be honest, I don't blame them. There is something very compelling about building a knowledge worker collaboration portal. Portal technology has been a solution looking for a problem [1]. Knowledge worker information management ("knowledge management") has been a business problem that has confounded technology for ages and only seems to get worse as the sea of unmanaged information grows. A "knowledge sharing portal" is a logical union of solution and problem and the success of SharePoint practically proves it. Who doesn't want a piece of that action?

Ingeniux's new Cartella product

Still, this does not mean that information management problems are on the verge of extinction. Even SharePoint's most ardent advocates concede that companies cannot cleanly codify all of its corporate intelligence with SharePoint alone. That takes governance, discipline, and investment beyond technology. But since implementing technology is always easier than affecting profound organizational change, there will always be a market for tools that promise miraculous results - just as there is always a market for easy weight loss programs and pills. These false promises of quick fixes have kept technology companies in business for years.

Even though market demand is huge, competing against SharePoint is not easy. For small to medium size companies and (especially) non-profits, it is hard to beat SharePoint on price. It is also hard to make the case about proprietary technology and lock-in to a potential customer that lives in Microsoft Office (as most knowledge workers do). Right now, alternatives to SharePoint are most attractive to companies that want to avoid building competencies in managing Microsoft servers and .NET development. It is going to take some bigger disruptions to minimize Microsoft's competitive advantage as a collaboration tool for the mass market. The big thing to look out for is a reduced supremacy of Microsoft Office file formats. This could be from an increased adoption of the Open Document format or it could be through a transition to "file-less" server side information storage like wikis or Google Docs. Until that happens, SharePoint killers will have the biggest success with companies that are reducing their use of Microsoft technologies on principle and with very large companies that are punished by Microsoft's per user licensing model. This is still a sizable market but hardly a threat to MOSS's core territory.

Notes:

[1] I can't even count the times that clients have initially used the word "portal" to describe their projects and later find that what they are looking for is just a regular informational website. Not a portal.

Jan 26, 2009

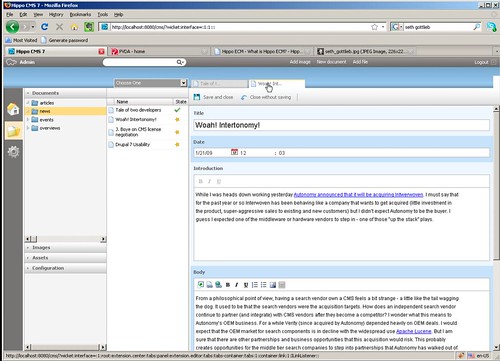

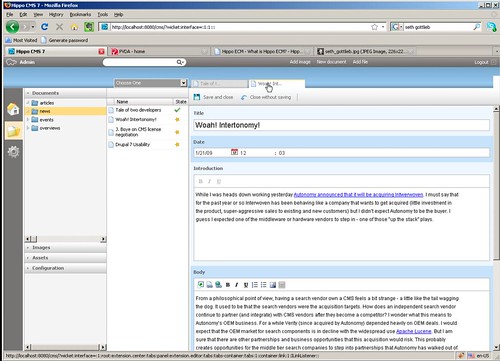

It's official. Version 7, a near-total rewrite of Hippo CMS, is now GA. Hippo CMS 7, formerly called ECM 1.0, is based on newer technologies Apache Wicket and JackRabbit. This new architecture gets Hippo off of the complicated, difficult to learn Cocoon framework and the retired Apache Slide project.

One thing that I particularly like is that they have achieved a compromise between the JCR's inherent hierarchical organization and a more free form faceted navigation. Hippo CMS 7 is designed for high content volume websites and shows a lot of thinking in this area. The faceted filters can be used at the API level by developers building websites on the platform. Unfortunately, this functionality has not yet been surfaced in the user interface.

As with earlier versions of Hippo, version 7's architecture has a clean separation between the repository, the management application and the front end delivery tier. Hippo CMS 7 gives developers a bit more of a starting point for building a front end website by shipping with a JSP tag library refers to display components managed in the CMS. Developers are still free to roll their own delivery tier using whatever display technology they choose. The standards-based Java Content Repository, plus frameworks like Sling, will make custom Hippo powered websites easier to build.

Hippo CMS 7 has a plugins framework that facilitates adding new functionality to the platform. There Hippo Forge site will be a place for the community to share their components and tools. These plugins surface on the dashboard and in other areas of UI and are better encapsulated than Hippo 6.x customizations.

On the UI side, Hippo CMS 7 shares some basic concepts with earlier versions of the platform. Version 6.x users will recognize the stateful tabs but will appreciate a new three column layout that allows a user to browse the repository and edit multiple content items at once (see screenshot). There are several other AJAX-enabled goodies like type-ahead search and linking and image placement through drag and drop. If you have seen Day's new CQ5 UI, there are some similarities there. In fact, an alpha of Hippo CMS 7 won second place in the Web Idol demo competition at the jboye08 conference last November. Hippo has plans to create specialized versions of the user interface to optimize the usability for specific user segments. For example, they are working on a user interface view that is optimized for power users on wide-screen displays that will maximize the use of the multi-column layout.

Being a new product, there only 2 customers live on Hippo CMS 7. Two more implementations are in progress. The documentation is not going to win Pulitzer but I have found the mailing lists to be very helpful. If you like what you see, I would recommend setting up some kind of arrangement with the Hippo team where they work closely with your implementation and they can submit fixes/improvements back into the core. Current 6.x customers will be supported by a dedicated V6 team who will maintain the platform with fixes and minor enhancements. No new support contracts will be sold for V6.

This is a big release for Hippo CMS. Usability-wise, there are significant improvements - particularly for power users managing large content repositories. Architecturally, CMS 7 offers a more modern technology stack that flattens the learning curve and enables more efficient development of the product. With a couple of successful implementations on the 7.x series, Hippo CMS may get it some deserved attention (particularly in North America where it is not widely known).

Jan 26, 2009

Angie Byron, has wonderful post on approaches to contributing to an open source project. She makes her point in parallel stories of an outgoing developer who puts a lot of intermediate versions of her code for public review and a perfectionist who holds back code that is not finished. Through the narratives, Angie shows how submitting lots of code helps leverage the collective knowledge of the community to learn better programming skills. Submitting code and interacting with the community also helps a developer build relationships with other developers who will be more likely to help her out.

With all of the focus on cost savings and intellectual property, the educational aspect of open source software is frequently overlooked - at least by business decision makers who have no idea how poorly written their in-house developed code is. Open source software has advantages over in-house software that extend beyond simply having more programmers eyes on the code; the ability to interact with similarly inspired developers across corporate boundaries can be a huge benefit that translates into professional development and job satisfaction. Of course, this value does not come for free. Like any other activity that builds skills, working on open source takes time. A manager should consider the educational aspects of open source software when developing a professional development program for his/her technology team. If you think of the time and expense of going to a traditional conference where a developer will, at best sit passively through conference sessions, working collaboratively on a real project either remotely or with developers at a sprint. This does not have to be limited to open source software but the open source licensing model certainly helps. There are some commercial products with active developer communities modeled after open source communities that share code and interact. If you have a large in-house development team, consider practices like pair programming, commit mailing lists, and code reviews that help turn programming into more of an open, collaborative effort.

A tale of two developers belongs on my "all time" open source reading list. Thanks Angie!

Jan 23, 2009

While I was heads down working yesterday Autonomy announced that it will be acquiring Intwerwoven. I must say that for the past year or so Interwoven has been behaving like a company that wants to get acquired (little investment in the product, super-aggressive sales to existing and new customers) but I didn't expect Autonomy to be the buyer. I guess I expected one of the middleware or hardware vendors to step in - one of those "up the stack" plays.

From a philosophical point of view, having a search vendor own a CMS feels a bit strange - a little like the tail wagging the dog. It used to be that the search vendors were the acquisition targets. How does an independent search vendor continue to partner (and integrate) with CMS vendors after they become a competitor? I wonder what this means to Autonomy's OEM business. For a while Verity (since acquired by Autonomy) depended heavily on OEM deals. I would expect that the OEM market for search components is in decline with the widespread use Apache Lucene. But I am sure that there are other partnerships and business opportunities that this acquisition would risk. This probably creates opportunities for the middle tier search companies to step into partnerships that Autonomy has walked out of.

Jan 20, 2009

Jean Marie Pascal, from Going to an OpenSource ECM World recently interviewed me about my thoughts on ECM and Open Source. JM has also done interviews with Jeff Potts from Optaros, Eric Barroca from Nuxeo, and Nancy Garrity from Alfresco. All of the interviews are rich with information about ECM and the unique perspectives of each of these individuals. Great idea Jean Marie!

Jan 19, 2009

Janus Boye has a great post on negotiating contracts with vendors. I usually try to keep myself out of contract negotiation but occasionally I am asked advice. I agree with everything Janus says and would only add that if you try (and are able) to take advantage of a vendor, it does not bode well for your future relationship. Like I have heard Graham Oakes say, if you don't try to make the deal a win-win, you will probably wind up being on the losing end of the deal. Hopefully, if you have gotten to the negotiation stage, you have found that you can work with vendor and can mutually benefit from doing business together. Work collaboratively to construct a deal that benefits both parties.

Jan 19, 2009

The Drupal 7 Usability Team is doing usability tests at the University of Baltimore. Drupal is one of the few open source content management projects that does formal usability testing and is so public about the results. Here is a nice short vlog showing Dries' reaction to usability testing done last year on Drupal 6 at the University of Minnesota. It shows how he took in the information, his surprise, and how he resolved to make adjustments. Also nice heatmap diagram of where the users looked.

Jan 15, 2009

The Plone Foundation, the non-profit that owns the Plone copyright and manages the Plone project, has initiated a program where Plone consultancies can sponsor the Plone project. In return for a $500 sponsorship fee, a sponsor will get its company logo placed on the Plone.net site (Plone.net is targeted at business people evaluating and using Plone) and the ability to place a Plone sponsor badge on its site. Premium sponsors will be placed on the top of the plone.net search results.

I think this is a good move for the Plone Foundation. It accomplishes the goals of helping Plone consultancies become more visible and it provides funding for all the great work that the Plone Foundation does. The $500 sponsorship fee is modest enough for individual practitioners to handle - especially considering all the benefit they get from being part of the Plone community.